When I first traveled to Tibet, my Tibetan teachers and friends taught me that Bon was the indigenous religion of Tibet. According to them, Bon gradually absorbed Buddhist ideas and practices over the centuries, evolving into a tradition that, today, closely resembles Buddhism in both doctrine and practice.

Tibetologists used to hold similar views. In 1956, an early Tibetologist, Helmut Hoffman, wrote, “The Bon religion, which was originally the national Tibetan version of North and Central Asian Shamanism and Animism, developed in Western Tibet, and particularly in Zhang-zhung; certainly under the influence of Buddhism and probably also under the influence of Persian and Manichaean teachings, into a syncretist system with a developed doctrine and a sacred literature” (Hoffmann, 1956/1979, p. 84). For years, I accepted this narrative as the established view. However, after research and reflection, I now believe that Bon was primarily a transmission of Buddhism that entered Tibet via Central Asia.

Here are some of the reasons behind my revised perspective:

- Bon as a religion made a late appearance in Tibetan history (early 2nd millennium). Little evidence exists for its earlier organization.

- The citizens of the Kushan Empire, which bordered Tibet’s western frontier, practiced fervent Buddhism for the three centuries of the first millennium AD.

- Similarly, the citizens of the Khotan Kingdom practiced fervent Buddhism on Tibet’s northwest border for most of the first millennium AD.

- The Bon tradition claims Persian (ཏ་ཟིག ) origins.

- The historical records show Tibetans in Khotan’s lands.

- The earliest Bon manuscripts were thoroughly Buddhist.

The following post gives more detail.

Challenging Bon’s Indigenous Status

In my previous post titled “Folk Religion in Old Tibet,” I explored how the anthropologist Ariane Macdonald (1971) proposed the existence of a distinct folk religion in early Tibet, separate from both the Bon tradition and Buddhism. Her research demonstrated the presence of religious beliefs and practices in early Tibet that fell outside the realms of both Buddhism and Bon, thus challenging the commonly held view of Bon as the indigenous Tibetan religion. Additionally, Macdonald’s findings cast doubt on the notion that Bon necessarily predated Buddhism’s arrival in Tibet (Bjerken, 2001). It is possible that the Bon tradition emerged alongside Tibetan Buddhism from India, rather than preceding it as previously assumed.

Bon’s late age

The notion of Bon as an ancient Tibetan religion has long been championed by Bonpo adherents. Some Bonpo have even claimed that their founder, Shenrap, lived over 18,000 years ago (Blezer, 2011b). If true, this would imply that Bon predated the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet by more than 15 millennia.

However, modern Tibetologists reject these claims of extreme antiquity as they also reject the idea that Bon was the pre-Buddhist, shamanistic religion of Tibet. Christopher Beckwith (2011) argued, “The still-dominant idea that Bon started out as a native Tibetan form of ‘shamanism’ is impossible to support on the basis of the evidence” (p. 174). Beckwith further noted that old Tibetan sources that refer to non-Buddhist beliefs and practices mention “folk religion” (myi chos [མྱི་ཆོས]), but make no explicit references to anything called “Bon.” In other words, “the fact is that we do not have evidence for any religious tradition called Bon in verifiable Imperial-period [600–900 AD] Old Tibetan texts” (p. 174). To be clear, the old texts mention Bon and Bonpo, but they do treat Bon as a religion. Instead, most indicators point to later dates for the appearance of Bon.

The beginnings of Bon – early 2nd millennium

Henk Blezer (2011a), a Tibetologist who wrote several articles investigating the beginning dates of Bon, stated “the construction or emergence of the main narratives of Bon identity all seem to converge in the beginning of the second millennium” (p. 155). During the Imperial Period, 600–900 AD, Bon had not yet organized itself into an identifiable tradition (Blezer, 2011b). In fact, one could even wonder if Bon might have a shorter history in Tibet than Indian Buddhism. “Bonpos claim to be older than Buddhism in Tibet, but the narratives appear later; so do the claimants, by all appearances” (Blezer, 2013, p. 196). But some evidence of earlier Bon thought does exist even if it was not a self-conscious Bon.

Bon written sources are relatively late to appear on the Tibetan scene: 10th to 11th c. [centuries] CE, at the very earliest. That late date probably directly reflects the late emergence of “organised Bon.” There are sources that are relevant to Bon and are at least partly earlier. These were some Dunhuang texts that do not “self-reference” as Bon but have similar content. (Blezer, 2015, p. 197)

Brandon Dotson (2008), another prominent Tibetologist, agreed with Blezer’s assessments about the age of Bon. Dotson also placed the institutions of the Bon religion in the tenth or eleventh century and credited Shenchen Luga (གཤེན་ཆེན་ཀླུ་དགའ་, Wylie: gshen-chen klu-dga’) and his disciples as the primary initiators of the Bon movement. While many Tibetologists have acknowledged the existence of Bon-related ideas and oral traditions prior to the 10th and 11th centuries, the scholarly consensus has maintained that Bon as a distinct religious tradition can be reliably traced to the tenth and eleventh centuries. However, Bonpo find such a stance disturbing.

The Tibetologist Samten Karmay (1998), a Tibetan Bonpo, complained that those same Tibetologists contradict themselves:

It is curious, to say the least, that for these scholars [specifically referring to Macdonald] there were in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D. Bonpo authors who were motivated by their faith to manipulate the terms bon/bod [བོན་/བོད་] and then assert that no religion called Bon as such existed before the eleventh century A.D. (p. 287)

But Tibetologist Rolf Stein (1985/2010) accounted for the use of the term Bon in the Dunhuang texts while remaining consistent with Blezer (2011a, 2011b, 2013, 2015) and Dotson’s (2008) analysis. Stein (1985/2010) articulated a theory of slow evolution in Bon thought, which I favor.

In the archaic texts, the Bon and the bon po already enjoy an important role. This Bon was certainly not yet the elaborated form that we find from the 11th century onward, but there is no break between the Dunhuang manuscripts and the later tradition. (p. 188)

Bon’s non-existent ancient script

In addition to discrediting the idea that Bon was extremely old, Tibetologists have also denounced the idea that Bonpo script preceded Indian Buddhist texts.

Eternal Bon literature abounds with tales of religious scriptures existing long before the historic epoch. … No archaeological or epigraphic evidence substantiating that pre-Buddhist inhabitants of Tibet had a system of writing has come to the fore. I, for one, have searched many grottos and rock faces in Upper Tibet for inscriptions pre-dating the seventh century CE. Given the absence of hard evidence, one can only view with a good deal of skepticism the notion that Tibetans could read and write in their own languages before the imperial period [600-900 AD]. It appears that this legend developed so that Eternal Bon adherents could claim their predecessors were just as literate as the early Indian Buddhists, a case of trying to culturally best one’s rivals. (Bellezza, 2014, pp. 221–222)

Therefore, Bon Tibetan texts cannot stand independent of the Indian Buddhism of Central Tibet. It was through the Indian Buddhists of Central Tibet that the Bonpo began to read and write Tibetan.

Indigenous and from the west?

Bonpo have stated that Bon originated west of Tibet (in ཏ་ཟིག) while simultaneously claiming to be the “the true custodians of indigenous Tibetan culture” (Blezer, 2013, p. 137). Bon cannot both originate in a foreign land and be an indigenous Tibetan religion; one cannot have it both ways. To be fair, with such close proximity to Central Asia, any religion in Tibet claiming to be free from outside influence is likely exaggerating.

Buddhism more likely

After Tibetologists have dismantled so many Bonpo claims, what is left? The most convincing theory is that from its inception, Bon was a form of Central Asian Buddhism.

David Snellgrove, Per Kvaerne, and Dan Martin [prominent Tibetologists] all concur that the quest for “pure” Bon, as the native religion entirely distinct from Buddhism, is mistaken. If one insists upon looking for the cultural origins of Bon, they suggest that one look for it as an alternative transmission of Buddhism originating in central Asia. (Bjerken, 2001, p. 218)

How so?

Snellgrove’s theory

The most historically compatible theory concerning the origins of Bon comes from David Snellgrove’s (2002) book, Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. The following is based upon, but not limited to, his thoughts.

The Kushan Empire (30-375 AD)

During the first millennium AD, two powerful empires emerged and declined to the west and north of Tibet. The first, the Kushan Empire (30-375 AD), bordered Tibet to the west. Kushan kings were ardent patrons of Buddhism, and it was from their territory that the first Buddhist missionaries traveled the Silk Road to China.

Map of the Kushan Empire, 2nd century AD.

Although a predominantly Buddhist state, the Kushan Empire also incorporated elements of Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, and Greek mythology into its religious thought. The similarities between Bon and Zoroastrianism’s dualism lend credence to the idea that Zoroastrianism significantly influenced Bon. The prevalence of Zoroastrianism in the Kushan Empire may also explain similarities between Bon and Zoroastrian origin stories, but these similarities are beyond the scope of this document. See Kvaerne (1987) for more on Persian influence in origin stories and Grenet (2015) for more on the religious composition of the Kushan Empire.

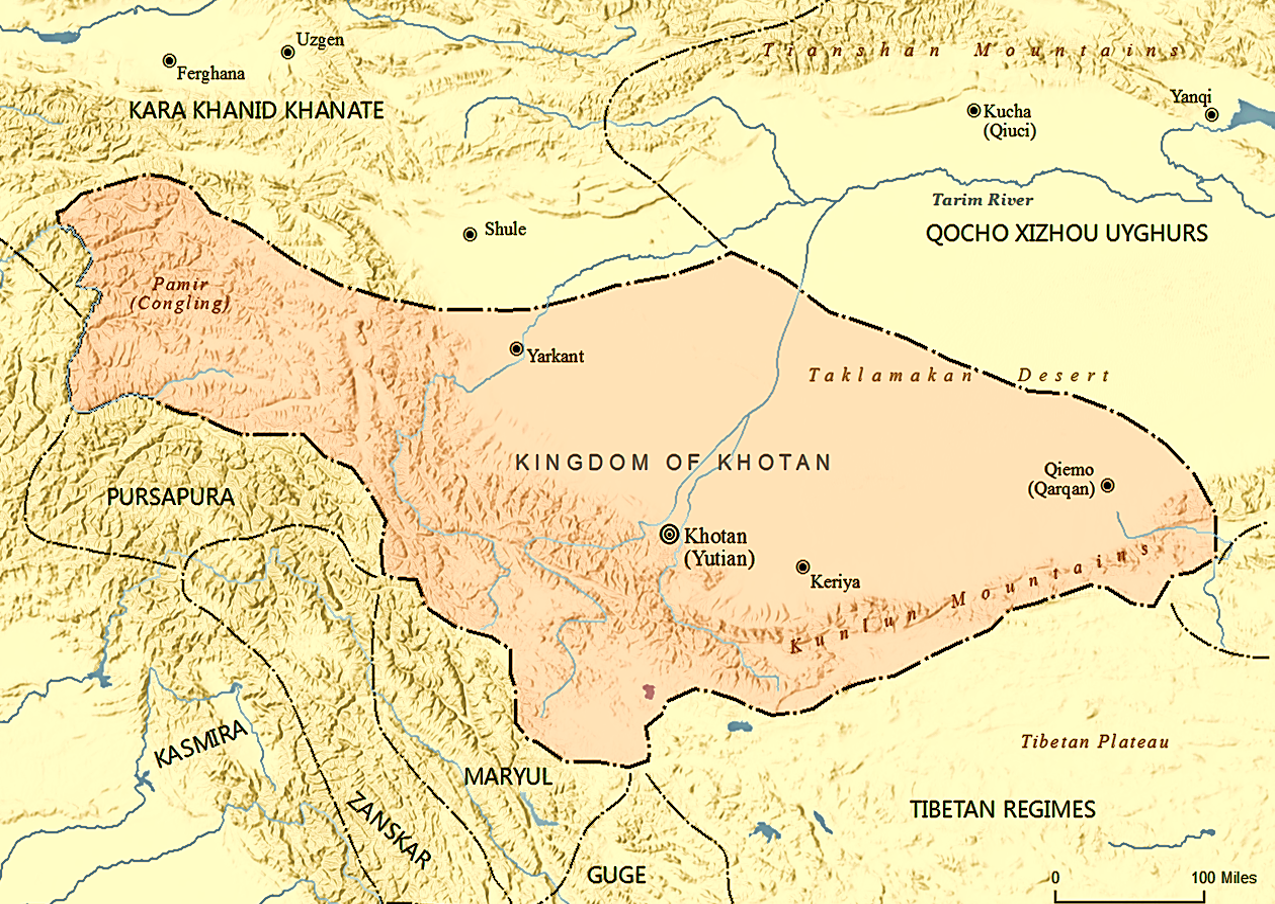

The Kingdom of Khotan

The second Buddhist empire that emerged close to Tibet lay to the northeast of the Kushan Empire and north of Tibet. Its heart was the oasis city of Khotan, presently a city of 400,000 people called Hotan in southern Xinjiang, China. Strategically located along the Silk Road, Khotan gradually evolved from a city-state into the Kingdom of Khotan. This kingdom emerged in the fourth century CE, flourishing as a center of trade and culture for over 600 years. In 1006 AD a Muslim, Yūsuf Qadr Khān, conquered the city and Khotan’s citizens gradually converted to Islam.

Map of the Kingdom of Khotan around 1000 AD.

SY, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Until 1006 AD, the majority of the citizens of Khotan were Buddhist. As early as the fifth century AD, a Chinese visitor documented the strength of Buddhism in Khotan.

This country [Khotan] is prosperous and happy; its people are well-to-do; they have all received the Faith [Buddhism], and find their amusement in religious music. The priests number several tens of thousands, most of them belonging to the Greater Vehicle [Mahayana Buddhism]. (Travels of Fa-Hsien, 414/1923, p. 4)

Snellgrove (2002) doubted that there were actually “several tens of thousands” of Buddhist monks. Nonetheless, it is clear that Buddhism was well established in Khotan by the beginning of the fifth century. But did Tibetans interact with the Kingdom of Khotan?

In the seventh century, the expansionist reign of Songtsen Gampo marked the beginning of Tibet’s territorial growth. This momentum persisted post-mortem, culminating in the Tibetan conquest of the Kingdom of Khotan. Frederick Thomas (1951), in his book Tibetan Literary Texts and Documents Concerning Chinese Turkestan, translated numerous Tibetan documents from the period of Tibetan occupation of Khotan. These translations included rosters of Tibetan soldiers stationed in Khotan and names of Khotan’s important Buddhist temples and monasteries.

These documents again affirm the strength of Buddhism in Khotan and also imply Tibetan interaction with those Buddhists. However, this interaction should not be over-emphasized. At the time of the Tibetan occupation of Khotan, Tibetan loyalties were divided between the Shang Shung dynasty in the western regions of Tibet and the Central Tibetan kingdom. Furthermore, the conquerors were from Central Tibet. It is unclear whether the Tibetan soldiers stationed in Khotan would have been sympathetic to Khotan’s Buddhist practices, as Central Tibetans, following Songtsen Gampo’s example, eventually adopted Buddhism from India.

What is clear is that centuries of sustained contact between Tibetans, Kushans, and Khotanese people likely catalyzed the Tibetan adoption of Buddhism from Central Asia. This cultural exchange ultimately contributed to the development of a distinct Tibetan religious tradition: Bon.

The Shang Shung Dynasty

The Shang Shung dynasty (ཞང་ཞུང་, Wylie: zhang zhung) beginning around 500 BC in western Tibet saw itself as independent of the Central Tibet kingdom which conquered it in the 640s (Ryavec, 2020; Snellgrove, 2002). Around the same time that he conquered the Shang Shung dynasty, the Central Tibetan king, Songtsan Gampo, introduced Indian Buddhism to Tibet. In Snellgrove’s theory, two streams of Buddhism now existed in Tibet: one stream introduced from India in the south and one stream introduced from the Kushan Empire and the Kingdom of Khotan in the west and north.

Resentful of their neighbors’ dominion, the Shang Shung people rebelled following the demise of Songtsen Gampo’s son, only for Central Tibetans to subjugate them once more. In response to this continued oppression, the Shangshung may have sought to differentiate their religious authorities from that of their conquerors by claiming their faith came from Persia (ཏ་ཟིག) rather than India via Central Tibet.

Isolation

Eventually the Bonpo of Tibet lost contact with their patrons in the west and north. “The Islamic conquests by ca. 1000 CE across South and Western Asia closed off any possible remaining cultural links and family ties” (Ryavec, 2020, p. 19). Bon subsequently remained throughout parts of Tibet, primarily dispersed along ethnic and linguistic lines (Ryavec, 2020). The ethnicities that had already converted to the Bon version of Buddhism resisted conversion to the Indian version of Buddhism that later dominated Tibet.

Snellgrove (2002) painted a possible scenario,

Lacking any organized structure for their religion as well as wealthy patrons, who could invite foreign scholars (as was later the case when Buddhism was introduced into central Tibet), the people of Zhang-zhung [Shang Shung] would assume that these religious beliefs and practices came from Ta-zig [ཏ་ཟིག, Dasik, a land in the west whose exact referent is unclear]. They would have heard of the great teacher who had first promoted such doctrines and they might well have used for him the title gShen-rab [Shenrab, the traditional founder of Bon] (“[his name means] best of holy beings”). Furthermore, when later they learned more of Buddhism from other sources, namely as transmitted direct from India in the eighth century and later, remaining staunch in their own already established tradition, they would quite reasonably urge that this same religion must have reached India from Ta-zig [ཏ་ཟིག, Dasik] and that Sakyamuni [a title for Gautama Buddha] must be either a manifestation of gShen-rab [Shenrab] or else just another religious teacher who was passing on gShen-rab’s [Shenrab’s] teaching in his own name. Only a theory such as this can explain the Bonpo claim that their religion comes originally from Ta-zig [ཏ་ཟིག, Dasik] via Zhang-zhung [Shang Shung] and that all Buddhist teachings, whenever they have learned of them, are already theirs by right. (p. 391)

Where is Dasik (ཏ་ཟིག)?

A note about the term Dasik (ཏ་ཟིག, Wylie: ta zig) above: the best definition that I have found came from Stein (1962/1972): “Their Chinese name of Ta-shih (ancient Tasig) comes from the Tajiks, an Iranian people, whence in turn we have the Tibetan Ta-zig [Dasik]” (p. 57). Thus, Dasik was probably not used with specific delineations but generally used for lands west of Tibet. But the Bon were not only from the Shang Shung dynasty.

Origins of the word, Bon

Beckwith (2011) traced the term Bon itself to the Chinese word for Tibetans, 蕃fán, used in the Sino-Tibetan Treaty Inscription of 823. Beckwith (2011) wrote that the Middle Chinese pronunciation of the word was “buan” instead of the modern “fan.” He suspected that the word was first applied to Tibetans in what is today northern Qinghai and southern Gansu. Tibetans themselves eventually adopted the word and self-identified as Bon in order to distinguish themselves from the Indian Buddhist Tibetans.

Bon as Oral Buddhism

Since Bonpo had no writing system of their own and only received their ability to write from the Indian Buddhists, one can assume that Bon was initially an oral tradition. Beckwith (2011) made the following distinctions. “Those who based themselves largely on texts, whether translations from Indic or Chinese originals or newly composed, are clearly to be identified with the ancestors of what later came to be called the Rnyingma [Nyingma, རྙིང་མ་] tradition” (p. 181). Nyingma is generally considered the oldest Buddhist sect in Tibet. As for the Bonpo, “The Bon ‘Tibetan school’ practitioners clearly followed their own largely oral tradition in the Tibetan language” (p. 182). When Bon texts finally did appear between the 11th to 13th centuries, they were “thoroughly Buddhist in nature—or at least not less Buddhist than some of the other texts recognised as ‘Buddhist’ (by non-Tibetan scholars)” (Beckwith, 2011, p. 173).

In summary, oral Buddhist believers from the Shang Shung dynasty had ethnic reasons to resist the Indian Buddhism flowing through Central Tibet. Oral Buddhists in northeastern Tibet also most likely began to differentiate themselves from the textually oriented Indian Buddhists. And perhaps those oral Buddhists sensing that they were different eventually adopted the term Bon from the Chinese label for Tibetans.

Implications of Bon’s identity as Buddhism

The above theory of Bon as Buddhism through Central Asia lends credibility to authentic Bon religion as a legitimate variation of Buddhism. It was not simply Tibetans adopting superior Buddhist religion without admitting to it. Bon is Buddhism in its own rite. As Central Asian Buddhism and Indian Buddhism encountered each other, they also influenced each other in ways that are today difficult to disentangle (Ryavec, 2020).

At one point in my life, I inwardly scoffed at Bon’s clumsy imitation of Indian Buddhism. However, my mockery was not justified. There is evidence that in some cases Tibetan Buddhist authors actually copied their texts from Bon manuscripts (Kvaerne, 1995) and not the other way around. The idea that Bon is actually a variety of Buddhism casts Bon in a very different light. Bon retains its doctrinal integrity (it wasn’t just copied) but it simultaneously loses its prestigious indigenous status.

Summary

In my first post, I argued that old Tibetan religion can most helpfully be conceptualized in three different categories: the folk religion (ཡང་གསང་ལུགས་), Bon, and Buddhism (Miner, 2024a). In my second post, I described what scholars know to this point about the folk religion (Miner, 2024b). In this post, I showed that Bon is not substantially older or more authentically indigenous than traditional “Tibetan Buddhism.” Instead, Bon is most likely an alternative stream of Buddhism that entered Tibet from Central Asia.

With the above understanding of the religious context in old Tibet, I am ready to explore the similarities between old Tibetan religions and Christianity.

Stay tuned!

Timothy Miner

I adapted the above from my dissertation Similarities between Early Tibetan Deities and the Christian God at Biola University in 2022.

______________________

References

Beckwith, C. I. (2011). On Zhangzhung and Bon. In H. Blezer (Ed.), Emerging Bon: The formation of Bon traditions in Tibet at the turn of the first millennium AD (pp. 164–184). International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies.

Bellezza, J. V. (2014). The dawn of Tibet: The ancient civilization on the roof of the world. Rowman & Littlefield.

Bjerken, Z. (2001). The mirrorwork of Tibetan religious historians: A comparison of Buddhist and Bon historiography (UMI No. 3000921) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan]. UMI Microform.

Blezer, H. (2011a). In search of the heartland of Bon—Khyung lung dngul mkhar the silver castle in garuḍa valley. In H. Blezer (Ed.), Emerging Bon: The formation of Bon traditions in Tibet at the turn of the first millennium AD (pp. 117–163). International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies.

Blezer, H. (2011b). The Bon of Bon: Forever old. In Emerging Bon: The formation of Bon traditions in Tibet at the turn of the first millennium AD (pp. 207–245). International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies.

Blezer, H. (2013). The paradox of Bön identity discourse. In H. Blezer & M. Teeuwen (Eds.), Challenging paradigms: Buddhism and nativism. Framing identity discourse in Buddhist environments. Brill.

Blezer, H. (2015). How Zhang Zhung emerges in emic and etic discourse and is ever at peril of disappearing again in the same: A brief survey of relevant results of the three pillars of Bon research programme (NWO Vidi 2005–2010). In Tsering Thar Tongkor & Tsering Dawa Sharshon (Eds.), མདོ་དབུས་མཐོ་སྒང་གི་གནའ་བོའི་ཤེས་རིག 青藏高原的古代文明 Ancient Civilization of Tibetan Plateau. མཚོ་སོན་མི་རིགས་དཔེ་སྐྲུན་ཁང་།.

Dotson, B. (2008). Complementarity and opposition in early Tibetan ritual. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 128(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/25608306

Grenet, F. (2015). Zoroastrianism among the Kushans. In H. Falk (Ed.), Kushan histories: Literary sources and selected papers from a symposium at Berlin, December 5 to 7, 2013 (pp. 203–239). Hempen Verlag.

Hoffmann, H. (1979). The religions of Tibet (E. Fitzgerald, Trans.). Greenwood Press. (Original work published 1956)

Karmay, S. G. (1998). The arrow and the spindle studies in history: Myths, rituals and beliefs in Tibet (Vol. 1). Mandala Book Point.

Kvaerne, P. (1987). Dualism in Tibetan cosmogonic myths and the question of Iranian influence. In C. I. Beckwith (Ed.), Silver on Lapis. Tibetan Literary Culture and History (pp. 95–104). The Tibet Society.

Kvaerne, P. (1995). The Bon religion of Tibet: The iconography of a living tradition. Shambhala.

Macdonald, A. (1971). Une lecture des Pelliot tibétain 1286, 1287, 1038, 1047 et 1290: Essai sur la formation et l’emploi des mythes politiques dans la religion royale de Sroṇ-bcan sgam-po [A reading of the Pelliot Tibétain 1286, 1287, 1038, 1047 and 1290: An essay on the genesis and use of political myths in the royal religion of Sroṇ-bcan sgam-po]. In A. Macdonald (Ed.), Études tibétaines dédiées à la mémoire de Marcelle Lalou (pp. 190–391). Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient.

Miner, T. (2022). Similarities between Early Tibetan Deities and the Christian God. Biola University.

Miner, T. (2024a). The three religious streams of Tibet | Tea House Conversations. ButterTea.World. https://sarasotamarketingdesign.com/2024/08/08/the-three-religious-streams-of-tibet/

Miner, T. (2024b). Folk Religion in Old Tibet | Tea House Conversations. ButterTea.World. https://sarasotamarketingdesign.com/2024/08/15/folk-religion-in-old-tibet/

Ryavec, K. E. (2020). Regional perspectives on the origin and early spread of the Bon religion based on core areas of monastery construction across the Tibetan plateau. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, 54, 5–27.

Snellgrove, D. L. (2002). Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan successors. Shambhala.

Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan civilization (J. E. Stapleton Driver, Trans.). Stanford University Press. http://www.scribd.com/doc/78298057/Stein-Tibetan-Civilization (Original work published 1962)

Stein, R. A. (2010). Tibetica antiqua III: Apropos of the word gtsug lag and the indigenous religion. In A. P. McKeown (Ed. & Trans.), Rolf Stein’s Tibetica antiqua: With additional materials (Vol. 24, pp. 117–190). Brill. (Original work published 1985)

Thomas, F. W. (1951). Tibetan literary texts and documents concerning Chinese Turkestan (Vol. 3). Royal Asiatic Society.

Travels of Fa-Hsien (399–414 A.D.), or record of the Buddhistic kingdoms (H. A. Giles, Trans.). (1923). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 414).

0 Comments